by Anna Correale

Summers at the trullo were sweet: pink geraniums bordered the entrance, a dollhouse-like turquoise front door. There were candies inside and shimmering pastel-coloured glasses, pink bedspreads, floral lamps, antique cups and saucers, nineteen-century whitewashed furniture, glass dishes, and pottery in various aquamarine hues, pink candles. Wildflowers were strewn across the pink and white table with its matching chairs, and the floor was light blue, while the wooden rocking horse was also painted in soft shades of pink and green. The trullo was like a lovely sugary toy, and the surrounding countryside was just as sweet and flowery. When we would arrive for the summer, yellow and pink prevailed, along with white and some iris and periwinkle blue shades. Buzzing insects, chirping birds, a swarm of sounds, and invisible lives were all around. Our senses spread and expanded or scattered like seeds in search of a new meaning.

We arrived with the children in June; Gianni was already sixteen while Violetta was just one year’s old: everything fermented. We took part in that swarm and overflowing life. We morphed into silence, bare feet, soil, dirty fingernails, shaggy hair—harvesting, probing, basking in the sun, eating with unwashed hands. We were one with the moon, grass, stones and much more, so much more, overwhelmed, in abandonment, grateful to that exuberance that kept us from thinking of ourselves.

The trullo sheltered and welcomed us inside its cool circular walls, protecting us from the heat and electromagnetic waves. From that mysterious human urge to grieve. From the inexplicable restlessness of our lives, which absorbed us thoroughly while in the city.

We spent every summer there from June to September, and we would not have wished to go elsewhere; it was not a holiday but a subverted life, a life opposed to the one we thought ours.

There were two palm trees in front of the trullo, limiting the entrance to a short staircase leading to me that all the farmers in the area used to beat their wheat on that court since it was the largest one around. Indeed, it was in the wide round court where Violetta used to play, staging in a sort of open-air circus, training animals and dancing. I would watch her through the palm trees while the approaching evening light turned to the same turquoise as the trullo entrance door; hence the scene became exotic: an illustrated Arabian Nights. It was amazing to see my daughter spin in the ring of the stone court, wrapped in the glittering blue evening, with her long blond plaits shadowing her movements.

The court also sheltered loads of freshly hand-picked almonds while drying in the sun. The surrounding field was mainly wooded with olive and almond trees. We spent at least an entire week in August harvesting almonds by beating the branches with long canes that we would find on the ground. Together with the almonds, leaves would fall, and myriads of small insects would scatter everywhere. Some ended in our eyes, mouth, nostrils. When beating the trees, we had to keep our heads down mainly to protect ourselves from the falling almonds and insects; it was a kind of ‘blind’ beating, although we could perceive the number of almonds and leaves landing on the nets. The children then enjoyed removing the husk from the inner shell, sitting on the chairs at the edge of the yard, while the local cat purred, often tagging along her kittens. We inevitably found new ones every summer and each time with different markings. The birth of Gigia’s kittens was, as a matter of fact, an established summer event. The safest corners around the trullo, the outdoor bathroom, the flowerbed under the rosemary bush, next to the entrance, under our parked trailer, was where mama cat would give birth. It was mainly Violetta and Pierre who spent hours making up games to play with our little summer pets. While the mother purred inexhaustibly. All this affectionate playfulness was carried out on the farmyard together with the shelling of almonds.

Once the work was done, the almonds formed heaps on the white sheets that we had previously placed on the court’s stoned ground to take them in every evening to dry. The damp of the night would have irremediably ruined them. Everything that happened took the form of a ritual, an irresistible summer game of which we never tired. It was something we looked forward to during the winter. The Trullo had a beneficial effect on us all. Perhaps it was, for this reason, that the children and I waited with yearning and anticipation for the summer to come. We wanted to save ourselves. We wanted to live the daily grind of a just life.

In the summer, my partner spent hours cutting grass, clearing the field from brambles, chopping the branches of the olive trees after pruning, arranging them in the woodshed, tidying up, cleaning everything, inside and out. I felt delighted with his efforts, which I thought devoted to the land and us, to our daily comfort. It never occurred to me that his hard work was linked to his profound fear of losing control over things, over everything that surrounded him. Everything had to belong to him. Indeed, that abundance of life, that overflow of nature and happiness, worried him tremendously. He felt threatened by it all.

But at least we had a little respite. All that physical work kept my partner from moaning about his discontent in life, fear of failure, and not being appropriately rewarded. Labouring seemed to absorb him to the point of forgetting us, keeping his mind clear of mankind, which he considered more threatening than anything else. For a few months, we were no longer the enemies, those who took away his time, those who did not allow him to maximize his artistic qualities, those who distracted him from himself. For a few months, we were relaxed, freed of responsibilities, forgotten. Abandoned to the pleasure of being in the world, which was beautiful, sweet and generous.

It so happened that the afternoon I was picking apricots from my beloved apricot tree: the most beautiful and majestic of the area, which produced tons of fruit that I used to make jam – that afternoon while I was under the tree with its tender leaves collecting those that had dropped for the wind and were excellent for jam, I was called by an old, hunched woman from the courtyard. She was dressed like an old-fashioned peasant. She had a black handkerchief on her head and a considerable grey skirt, which probably covered a further one. Her wrinkled face, whose spots were accentuated by freckles that usually affect redheads, had two very green eyes; they seemed small as she squinted to protect them from sunlight. I walked up, trying to get closer to her, but she stopped me, pointing to a stone right beside my foot. She told me to keep it. I barely understood what she had just said; I wasn’t sure if she had spoken in a dialect or a foreign language similar to Italian. I bent down to fetch the stone, and when I looked up, the old lady had vanished. I looked around, then went to look in the field and in that of our neighbour without finding her. I stood there with the stone I had just picked up, giving it a better look. Like many others found in the area, it was an ordinary stone, very smooth and slightly elongated. It was pleasant at the touch. It fit perfectly in my palm, I looked at it again, and then I went back into the trullo and placed it on my bedside table.

In June, I had harvested the apricots and collected the stone. At the end of August, while I was resting in the cool of my bedroom, a car turned up, driven by a woman I did not recognize. She was probably a tourist who had lost her way looking for information. She got out of the car when I went up to her. At first, I thought I knew her; she had a familiar face, her green eyes shone on tanned and freckled skin, a beautiful woman in her fifties, dressed in white with radiant, reddish hair. Convinced of having to give her directions, I approached her with indifference. The woman was from Turin and asked me if she could visit the trullo because it was there that she was born and had spent her childhood. This triggered my curiosity immediately. I let her in, asking her to tell me how they had lived and how many people had resided in the trullo, whether her childhood had been a happy one and her family’s life pleasant. Dropping all formalities, I pressed her for further details. Despite the evident asynchrony, I probed for an intimacy I thought legitimized having shared the same house. The children, she said, slept in the alcove of the main trullo that was also used as a dining room; the parents in the smaller room next door. A few steps below dug into the rock adjacent to the oven was a shelter for a goat and a few chickens that only a wooden door separated from the rest of the house.

They cooked in the fireplace and washed using an outdoor bathroom, heated with a brazier in winter. The trullo had belonged to this lady’s family for generations until her sister decided to sell it on the death of their parents. A fishmonger, the previous owner who lived by the sea and had never lived there, bought it. The trullo had come to us as his family had left it, and we had left it just as it was. We were in awe of those hand-cut stones perfectly posed one on top of the other without any mortar; of those indoor plasters a mixture of straw and clay, dating back at least a century, of all that laborious and meticulous work that had made the trullo untouchable.

The woman seemed to be very moved and grateful for our sensitivity. The visit did not last long; she went away, leaving me with the same sense of loss in which the old woman in the courtyard had left me. In that void, in which I remained for a few minutes, the extraordinary resemblance between the two women emerged. I felt lost in that time maze, in which disappearance heralded the appearance and vice versa. Past and present met at the very moment in which they subverted to remain united in that sense of loss in which they left me.

Then the summer went on as always, and the stone remained silent and unbroken on my bedside table. When I returned to Naples, I took it with me and closed it in the small dresser drawer in the bedroom, forgetting it.

The years that followed that summer were bitter. My mother passed away, and soon after, I became seriously ill. Then my partner left with a chilling, cunning plan, equal to that of a serial killer. I found out that not only had he never loved me, there had not even been the vaguest idea of appreciation; the children, between pain and adolescence, were lost.

So, I left, moving to Paris for a few years. And for some time, I stopped caring for everyone; I only took care of myself.

Taking care of myself, my children also began to recover. They, too, began to feel better. Everything started to move once again; a new life crept up between us like a snake awakened from Spring, slow, sinuous, voracious. All had to be redone, rebuilt: our love, our bodies, our home. I could never go back to my home town, Naples, for sure. Although Paris had welcomed and protected me, it was not a place where I could realistically decompress. I needed nature to learn, to change. I asked myself where had been the place I had felt best in my life, and the answer came clear and immediate: in the countryside, in my trullo. So, I mustered all the courage I could and returned to Puglia to build my new home in the same area where the trullo stood. I needed something new. Building a house represented rebuilding myself. It was symbolic. I had to start from scratch; a new place was crucial.

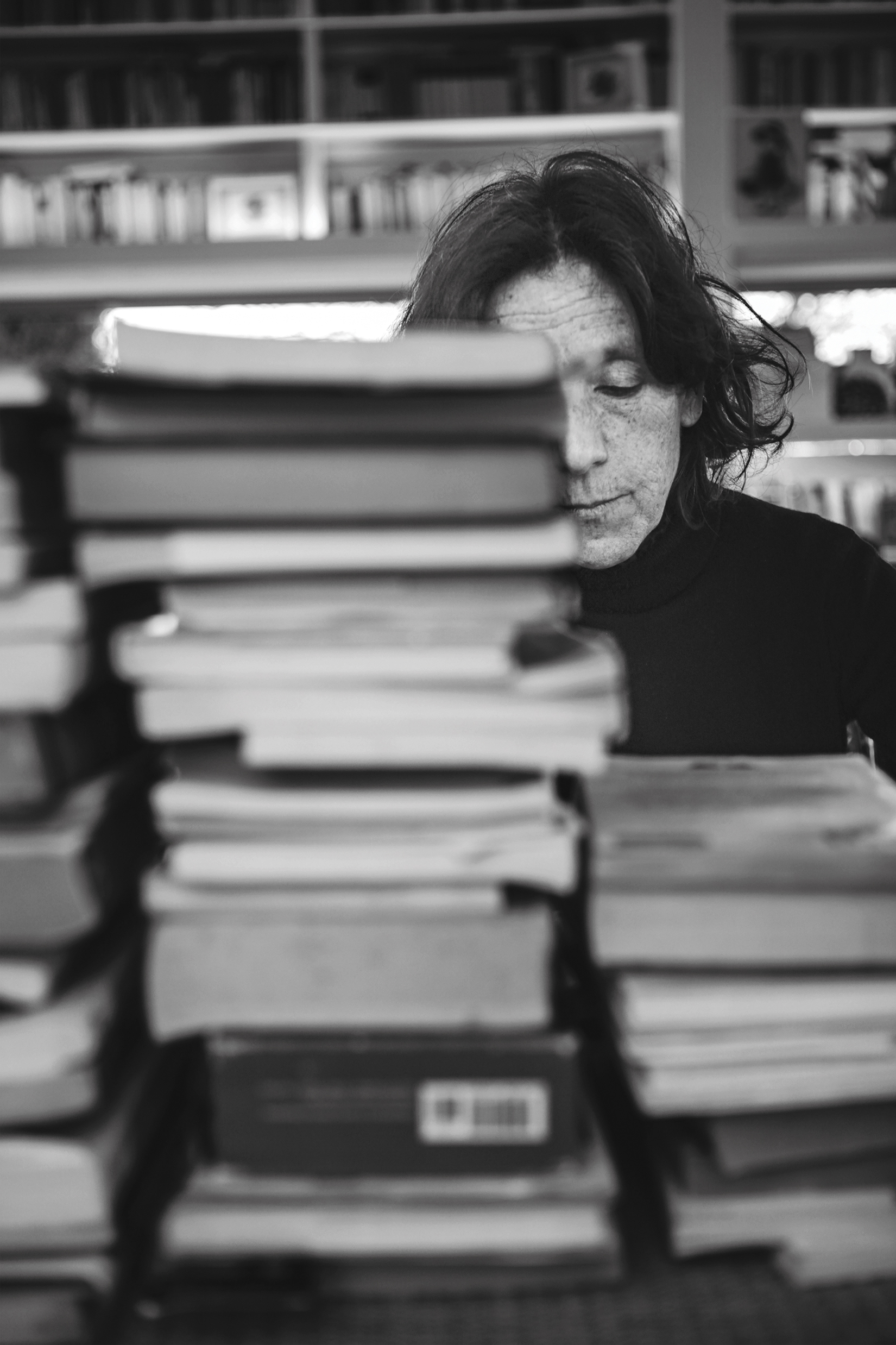

I dedicated myself with incredible energy to its design. I needed light and a wall for the bookcase, which was missing in the trullo since the walls were curved. I had already decided to abandon everything I had in Naples except for my books. I was not going to bring anything else with me from my past. The construction of the new house was demanding; it took over a year to build. When the works would cease for some reason, I felt a knot inside. Fear of affirming myself, being there, feeling complete: the construction of the house was linked to my feelings. But I also felt enthusiastic: it was coming up well. Without ever having shown great interest in architecture in general, it rose under my eyes and under the hands of the alternating labourers. I admired their ability to build a pillar, an attic, a wall, a doorway. In the end, I tried to furnish it with what I had spared from the trullo and furniture that I found at flea markets. I began a new life there with gratitude, while the large bookcase, which had been built by my son Gianni since in those years he had learned to do woodwork, remained bookless for a long time. I felt I didn’t have enough emotional strength for that move, which, in the end, Gianni organized with a truck from Puglia.

A few cardboard boxes arrived in the new house and stationed on the floor, in the hall’s centre, for months. Slowly, I opened a box at a time and rearranged the books. I did it with anomalous effort coming off as the most tiring thing I had ever done. I noticed that the arrival of belongings from Naples, albeit books, put me in a state of anxiety. It was challenging to reintegrate that part of my past into my present. I would have preferred leaving the past out, but I knew that doing so, especially with the books I had loved so much, helped me find new stability. In addition to the books were boxes full of documents and photographs, which with even greater effort, I rearranged in containers I had bought new as to renew what they held inside.

It really took me months to rearrange and reorganize everything; I did it exhaustedly, slowly, almost forcing myself. As the bookshelf filled up, it actually came to life. As a whole, the house became more habitable; the books gave shape to space, I was in good company. I also tried a different way of cataloguing, linguistic cataloguing for literature and chronological for philosophy, the other subjects instead I left unchanged not to tire myself too much.

At one point, I threw out the last cardboard box that had contained old documents that I slipped hastily into a plastic container, which I placed straightaway in the mezzanine without even checking what was inside. In short, I was able to find a sense of order. The feeling of euphoria far exceeded satisfaction.

At that moment, I realized that from the house in Naples, I had also brought two chairs and the small dresser I had in the bedroom. Taken by the desire to prolong that state of happiness, I placed the furniture where I had envisioned it without wasting too much time: two chairs, a desk and the dresser at the end of the bed. Before filling the dresser, I decided to clean it; I opened the top drawer and found the stone that the old woman in the courtyard had pointed out to me, smooth and easy to hold like a sword handle. I held it in my hand, feeling the archetypal courage of a warrior. I clenched the stone a few minutes before the mirror: I was attired in a leather armour of an Amazon. I was invincible.

Anna Correale

She graduated in Philosophy from the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy of Naples “Federico II”, with a dissertation in Moral Philosophy on Gilles Deleuze.

For a long time she was a scholarship holder at the Italian Institute for Philosophical Studies, for which she published the following articles: La parola metforica come accadere; Le immagini dell’uomo nell’antropologia filosofica del novecento; Filosofia come metafilosofia; Critica dell’ontoteologia, which appeared in the journal Informazione Filosofica.

She reviewed Gilles Deleuze’s La piega – Leibniz e il Barocco, and Jacques Derrida’s Dello spirito – Heidegger e la questione, for the journal Filosofica Discorsi, edited by the University of Naples. She published a short essay on Margherite Duras entitled La scrittura dell’erranza dell’amore, in Passaggi di confine (edizioni C.P.E.), Naples.

Translated from French Francoise Collin’s essay entitled La paura – E. Levinas e M. Blanchot, collected in Il Vivente (Filema editions). She translated from French Marguerite Duras’ novel L’estate 80, (Filema editions). She obtained a PhD in philosophy from the University of Nice “Sophia Antipolis” with a thesis directed by Professor Daniel Charles entitled L’écriture du silence. In 2007, she published a collection of short stories entitled Dove noi siamo (published by Dante & Descartes). In 2011, she published a novel entitled Perché io non spero più di ritornare (Palomar editions). In 2013, she published the text accompanying Massimo Latte’s paintings entitled Supplément d’amour (La Barque editions). In 2017 she published Wendy, poetic prose illustrated by Patrick Depin (Pietre Vive editions). She currently lives between the Apulian countryside and Paris.